An Urban Lens on Presidential Immunity

Yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a major ruling in the case known as Trump vs. United States. The case was brought by former President Donald Trump to dismiss all Federal charges against him for allegedly criminal behavior for actions he took while he served as the 45th President of the United States.

.

For the benefit of our readers who are outside the U.S. (about 45% of current subscribers), former President Trump currently faces two different Federal-level criminal prosecutions. The first is for his actions prior to January 6, 2021 to prevent Congress from formally certifying the results of the 2020 election and for the role he played in instigating the violent attack by his supporters on the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021. The second is for his refusal to return classified documents that he took with him to his home in Florida as President Biden was being sworn into office on January 20, 2021.

Trump’s lawyers argued that anyone who is elected to the office of President is granted by the U.S. Constitution the privilege of absolute immunity from Federal criminal prosecution for any action taken while serving in that high office. In making this broad claim of Presidential immunity, Trump’s lawyers even offered the extreme hypothetical example that a President could order a team of U.S. Navy Seals to assassinate a political rival without fear of criminal prosecution unless that President was first impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives and found guilty following a trial by the U.S. Senate.

Trump’s arguments echoed comments once made by Richard Nixon in a famous television interview with David Frost. Frost asked Nixon if a President was permitted to break the law in situations when the President decided “it’s in the best interests of the nation or something.” Nixon famously replied by saying, “Well, when the president does it, that means it is not illegal.”

Despite the widespread and bipartisan rejection of Nixon’s point of view (first broadcast in May, 1977), the Supreme Court opinion released yesterday authored by Chief Justice John Roberts came to a very different conclusion.

The Roberts opinion, passed by a 6-3 partisan majority, divides all actions done by a President into three categories: 1) official acts “within his conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority;” 2) official acts that are less central to the President’s exclusively granted Constitutional authority, and are thus “within the outer perimeter of his official responsibility;” and 3) unofficial acts, which may include times when the President speaks as a “candidate for public office or party leader.”

The opinion concludes that all Presidents have absolute immunity from prosecution for any official act that falls within Category 1, without exception. In addition, all Presidents are presumed to be immune from criminal prosecution from any official act that falls within Category 2 unless prosecutors can overcome a very high legal bar described within the opinion. Furthermore, the Roberts opinion explicitly states that Presidential immunity for official actions cannot be removed even by evidence of a corrupt motive. Motives are defined as irrelevant to whether an action is official or unofficial. As for Category 3, Presidents have no immunity for acts that are found to be unofficial, as long as a Federal court carefully reviews the facts in any complaint and concludes that the President’s actions are indeed unofficial.

The opinion further elaborates by taking these principles and applying them to some of the specific facts that are alleged in the two Federal criminal indictments Trump now faces. The Roberts opinion concludes that many of the allegedly criminal acts are within Category 1.

For example, Trump is charged with criminal conspiracy by threatening to fire the Acting Attorney General and other appointed officials of the U.S. Department of Justice unless they agreed to aggressively push state election officials and governors in December of 2020 to decertify vote counts and appoint official electors from their states who would vote for Trump in the Electoral College without having any evidence of illegal vote tampering.

The Roberts opinion concluded that Trump’s actions are totally immune from criminal prosecution because they fell entirely within the Constitutional authority of the President. The President, Roberts argued, has full authority to direct the actions of any Executive Branch agency, including the authority to fire any appointed official without exception. (The officials refused to comply but were not fired.)

Trump is also charged with criminal conspiracy based on his conversations with Vice President Pence. The law gives the Vice President the authority to oversee the ceremonial certification of election results by Congress, which is required by law to happen on January 6th. Trump pushed Pence to use that ceremonial role to block the certification based on baseless claims of state-level election fraud. (Pence also refused to comply).

Roberts concluded that Trump’s discussions with Pence fell into Category 2, which creates the strong presumption that his actions are immune from any criminal prosecution, regardless of the content of those discussions. Anytime a President discusses anything with a Vice President, it is an official act and thereby immune from any criminal prosecution.

Within the Constitutional design of the U.S. Federal government, the categories for Presidential actions that are defined in the Roberts opinion released yesterday in Trump v. United States now have the force of law. This creates a remarkable expansion of Presidential authority.

But how does this new authority relate to American cities? After all, the U.S. Constitution doesn’t even mention cities. The Federal government is a political union of states. Cities were not relevant entities when the U.S. Constitution was written in the summer of 1787. Today every state has two members of the U.S. Senate, and the 435 current members of the House of Representatives are apportioned as evenly as possible among the states, as long as each state, no matter how small, gets at least one. The President is elected by the Electoral College, whose members are appointed by state governors based on each state’s popular election results (almost all are “winner take all”) and that state’s total number of Senators and Representatives. Cities play no direct role in any of these governance mechanisms.

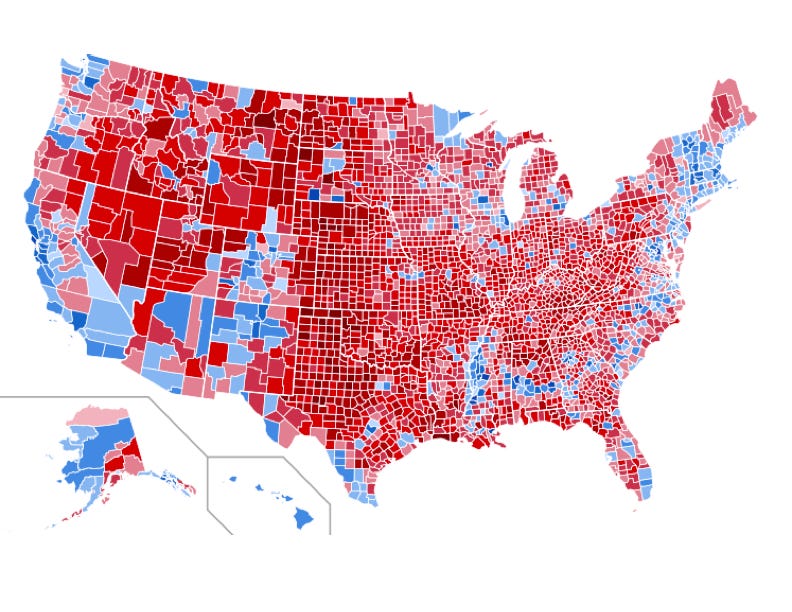

But underneath the official veneer of the Constitution’s governing mechanisms, cities play many essential roles in the politics of America, and in American prosperity. The Electoral College process of electing Presidents makes American elections look like they are dominated by a sharp divide between “Red States” (Republican) and “Blue States” (Democrats). Yet the reality is seen more clearly by maps like the one below that show election results by county.

Presidential Election Results 2020, by County

Red = Trump; Blue = Biden

Source: Magog the Ogre, WikiMedia Commons.

Every so-called Blue State contains many, sometimes a majority, of counties that are Red. And every so-called Red State contains many Blue counties. Oklahoma and West Virginia are the only Red states that have no Blue counties. And every Blue State has at least one Red county, except Hawaii. America’s political divide is not between states, but rather between urban and densely populated suburban counties (Blue) and rural and less densely populated suburban counties (Red).

This underlying, broader urban vs. rural, dense vs. less dense political voting pattern within and across most states creates the broad political foundation for the system of urban policies that exists in the U.S. This system contains a great deal of ambiguity in the Federal politics of Congressional legislation, the Federal politics of how Presidential authority translates into Executive Branch implementation of Federal laws and the priorities of Federal spending of Congressionally approved budgets, and each state’s own internal politics of rural vs. urban policies.

Politically, almost all major cities in the U.S. are run by Democrats. The U.S. Conference of Mayors, for example, includes 1,400 elected mayors from U.S. cities with more than 30,000 residents. The organization is non-partisan by definition. And its own bylaws require that at least one of its top three governing positions must be held by a mayor from “the minority party,” i.e. a Republican. But Republican mayors are rare, especially from big cities.

The vast majority of big city mayors are Democrats. Even so, the organization leverages its authority over its members to seek pragmatic policies and reforms that shy away from national political partisan divisiveness and that minimize the impacts of state-level divisive politics.

This multi-level political system insulates cities somewhat from sharp partisan swings in national politics, and equally sharp swings in State-level politics. Red mayors can work with Blue mayors to balance political divisions when necessary to keep urban policies on an even keel when possible. Mayors are problem-solvers. Few seek divisiveness.

Yet the balancing act that insulates urban policies from divisive national political shocks has emerged in an era defined by relative stability in the political use of Presidential authority. Stability has been reinforced by political norms of moderation, a strong Federal civil service based on non-partisan expertise, and a healthy degree of uncertainty about the boundary between politically-driven policy preferences and criminally liable political and/or corrupt interference in well-established Executive Branch processes.

The Supreme Court, however, just changed the rules. The President now has full immunity from criminal prosecution for any use of her/his power to direct and/or to interfere with the actions of the Executive Branch agencies that report to the President. The President’s motives for any executive branch activity, including the Department of Justice’s authority to mount civil and/or criminal investigations of any person, agency, government official, or governmental organization cannot be questioned as part of any legal challenge based on improper or corrupt actions.

Presidential authority within the Executive Branch now has virtually no checks or balances. The Roberts opinion in Trump vs. United States grants the President the power to demand obedience on almost any Executive Branch matter, whether driven by ideological fervor, political vindictiveness, favoritism, discrimination, or even outright corruption. Motives play no role in assessing the President’s authority to demand actions. The President’s immunity is total for Category 1, and almost impossible to challenge for Category 2.

All of this new power, however, is kinetic potential. The degree to which these new Presidential powers disrupt the complex political system upon which cities depend for their survival in a Constitutional governance structure that does not recognize their importance rests on the willingness of a President to use these new powers.

Former President Trump has made it very clear he intends to demonstrate the full extent of the new powers the Supreme Court has now created for the Presidency if he is reelected in November of 2024. He promises to test every boundary. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 report has already created a clear roadmap for forceful Presidential action based on its preferred ideology and policy preferences for each part of the Executive Branch. Candidate Trump has repeatedly listed a series of perceived grievances and political targets he intends to act upon if he has the opportunity.

It is possible that President Biden could also make new use of these expanded powers if he wins a second term. Although his governing style has moderated many of the political demands he gets from more Progressive members of the Democratic Party, the new rules just created by the Supreme Court could change his governing style in many ways.

One thing seems clear though. U.S. cities are about to be caught in the cross-fire as the political system that has evolved to provide them some shelter from the deep political divisions that exist within U.S. politics is about to enter an unpredictable period of uncertainty. The pragmatic problem-solving capacity of American mayors, both Blue and Red, may be lost quickly as the American political system struggles to adjust to a turbo-powered American Presidency.

Bob Gleeson

Source: Substack

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments